Building live collaboration in Rust for millions of users, part 4

Next stop: realtime editing for everyone

Since the first part of this blog series, we have been saying that the key motivation for moving I/O driven parts of the logic into the Photoroom engine was the intricacies of realtime collaboration. With its tricky streaming I/O, network reliability needs and editing conflict resolution, we really did not want to maintain 3+ implementations of it. In the previous parts, we’ve discussed the foundations required to make it work. Today, it’s finally time to look at how this feature set works under the hood.

The basic idea is very simple - when you and your teammates open the same project in the editor, you should see each other’s presence, and edits made by one of you should be seen, in real time, by everyone. Needless to say that making that work at long distances, where speed of information exchange is limited at least by speed of light, but more often than not by the speed of a mobile internet connection on a train, brings a level of complexity.

How it started vs. how it’s going

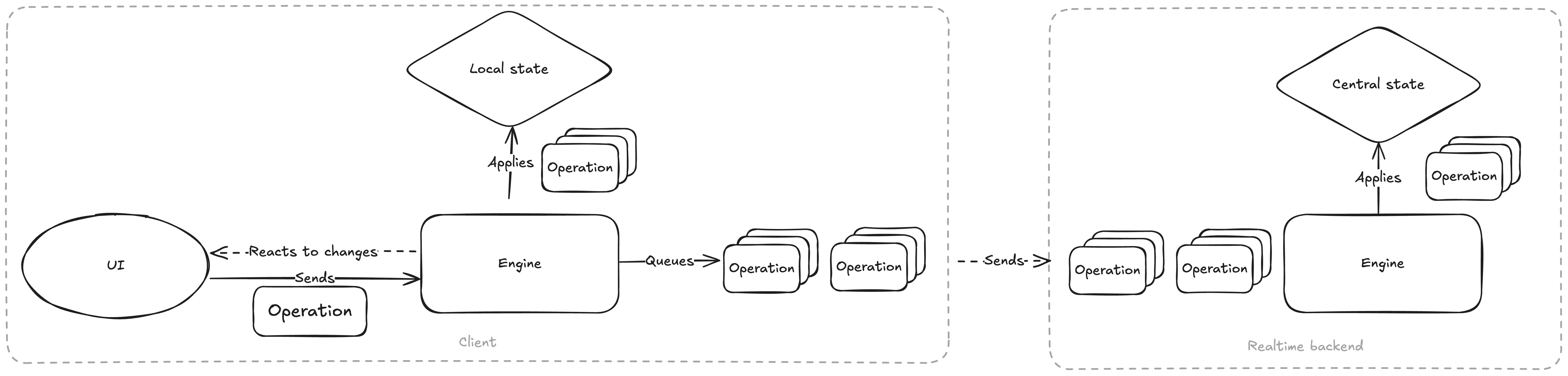

At the heart of the realtime collaboration is our project editor. In its early versions, this was written in an imperative way. Reading the code, you would see logic along the lines of “when button A is clicked, attribute B of object C changes to a new value, and image D needs to be refreshed”. Moreover, each platform implemented these edits slightly differently. That made it pretty much impossible to send the edit operations over the network, so we knew we had to switch to a different approach - event sourcing.

Familiar to web developers from Redux, and used as the foundation of Crux, event sourcing is based on the idea that the state of the project is a result of a sequence of user operations. Since the only state changes made are a result of the operations, the log of operations is the only information required to reconstruct the state, and at least in theory, multiple sequences of operations (from different collaborators) can be merged to arrive at the final shared state of the project.

With this in mind, we introduced a new component to the engine, called the Mutator, whose job it is to maintain the state of the project, and update it in response to the user’s actions, expressed as operations. There’s an explicit, finite set of operations the user can apply. As a nice side-effect, this approach makes it relatively easy to implement an undo stack: so long as we can create a reverse operation every time we apply one, we put it onto the undo stack, and use it when undo is requested.

Enter diffs

We ended up calling these lower level edit operations “diffs”. Diffs operate on the project tree as if it was a flat list of objects, each with a stable, unique ID - roughly speaking a path in the project tree structure - and a set of attributes. Object can be added, removed and their attributes can be set to a new value. As a protocol, this is quite a bit more stable and open to non-breaking changes in the future (we also added a versioning system which lets us make breaking changes abandoning older clients if we absolutely have to).

The updated Mutator now takes the user-initiated operation, converts it to diffs, applies those diffs to the local state to provide a smooth user experience, and sends the diffs to the realtime backend. It will in turn apply the diffs to its copy of the state, broadcasts them to other collaborators and periodically saves the state to the database.

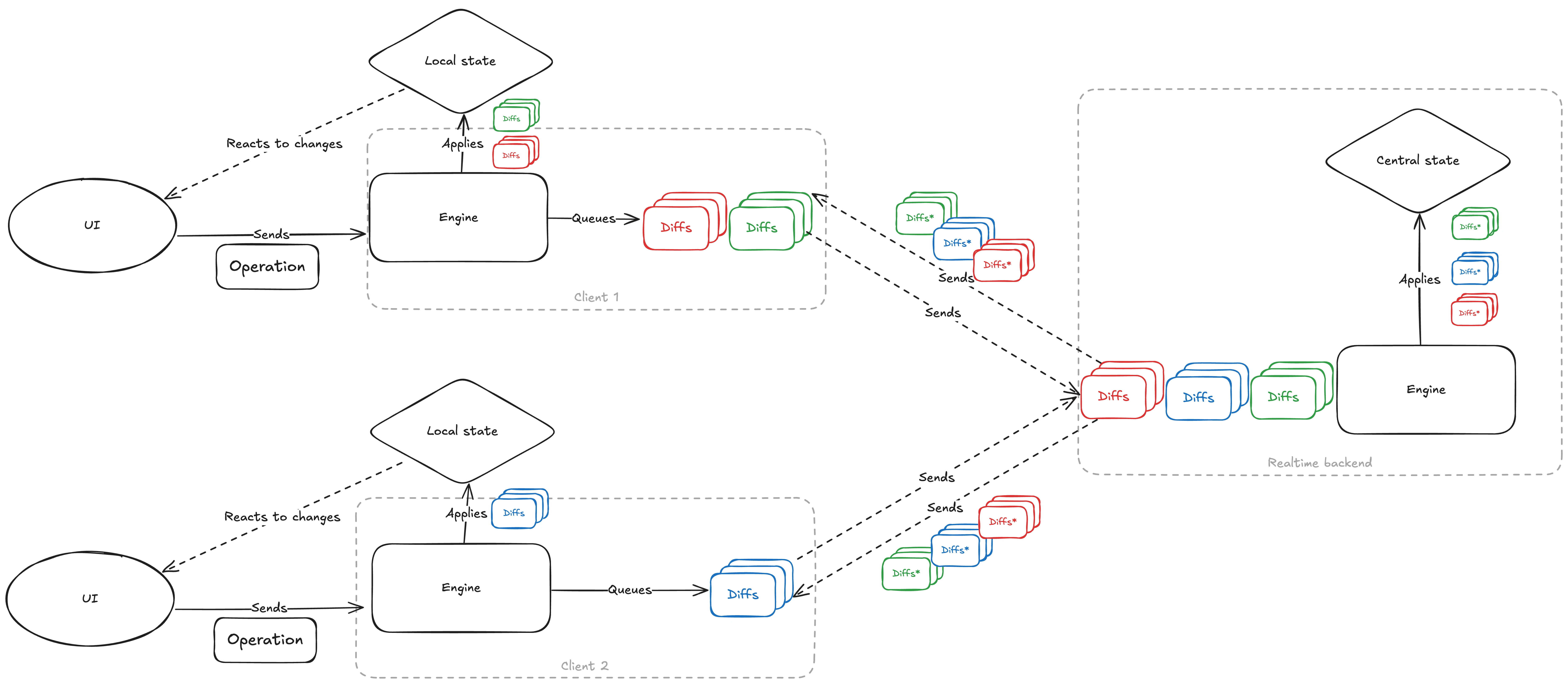

And that’s it! … No just kidding, that’s not even remotely it 🙂 There is one big problem - collaborators might make edits simultaneously, based on their local state, before edits from their peers arrive. Those edits can, and will change the same attributes of the same content in conflicting ways, edit content removed by someone else, etc. To get collaborative editing working reliably, we need to handle those situations - we need some sort of conflict resolution.

Conflict resolution

As a basic strategy, we decided that because our users see each others work in near real time, they are aware of which part of the document everyone is modifying. By indicating who is modifying what, we are implicitly teaching our users about conflict resolution and can adopt an easy resolution strategy: the last arriving edit will win. So long as all users converge to the same state, any unwanted edits this causes can easily be fixed manually. This almost works, but doesn’t address scenarios where the realtime backend receives diffs for objects that have been removed by another user or attempts to insert items into a list at the same position (in our case it’s the z-index of layers).

So in practice, our backend can respond to a Diff in one of three ways

Accept it as it

Drop it, because it makes no sense (it edits an object which no longer exists)

Amend it to be compatible with other edits

The last case resolves attempts to set the same z-index already used by another layer. For this we use a strategy called fractional indexing, first described by Figma, where z-index is, roughly speaking, a real number (with a decimal part). Fractional indices can always be sorted, and it is always possible to create a fractional index which sorts between two other indices (as if we’ve taken the mid point between them). This lets us always create indices that sort consistently.

That solution trades one problem for another. The diffs accepted in the backend are not necessarily the same diffs we will receive back as an acknowledgement. For one, there can be diffs from other collaborators mixed in, but even our own diffs may have been changed to fit the other edits. The final trick to make the protocol work is a familiar operation from git: rebasing. When a client receives the diffs back from the backend, it first unwinds its own local diffs to the point that has been previously acknowledged, then applies the modified diffs arriving from the server. This works because like operations, diffs can be inverted and their reverse applied.

And that really is it. With this strategy, all the collaborators eventually arrive at the same state. And just to make sure that is the case in production, we added convergence checks to the protocol - when the editing settles and there is a quiet period, the client sends the backend their full state and the backend compares it with its own copy. Any disparities are treated as an error and alerted on. This does still happen on occasion, but at the time of this writing, it happens about once a day, while there are on the order of ten thousand live collaboration rooms active at the same time.

How about undo/redo?

The diff system has one nice side-effect: the undo stack just works. When a mutator receives an undo operation, it pops the inverse operation created earlier from the undo stack, converts it to diffs and broadcasts it. From the perspective of other collaborators, it’s simply another edit. It also means the undo stack is local to the user, in other words, you cannot undo edits you didn’t make.

Messaging infrastructure

Now that we understand how the edit operations are exchanged between the connected users and the server and applied with eventual consistency, we also need to solve for the messaging infrastructure. We need to ensure that the messages are guaranteed to be delivered, that the connections are monitored and restored when lost, etc. No smart protocol can make up for information that wasn’t exchanged.

First we made the decision to go with WebSockets as the transport. We knew they have been used for this type of use-case before and scaled successfully, and they are ubiquitous across platforms. But they are also quite simple and low-level. They allow a single connection to a URL, which establishes a single two-way stream of messages, much like TCP. They do not provide any mechanism for acknowledging messages, or for restoring dropped connections automatically (in fact even detecting a disconnect is not trivial).

What we need is all of those things and then some. We need to have multiple separate message streams so that different realtime features can have a separate “topic” they are interested in (such as presence, edits, selections and cursors, …). Our users work on their phones, which means we need message acknowledgments in both directions, so that if there is a temporary connection drop, we don’t lose the information and allow the state of the client and the server to diverge. We need to know when connection has been lost, even if the underlying WebSocket appears to be connected, and we need to automatically reconnect and resend all pending messages (those which have not been acknowledged) when that happens.

Thankfully, this is a very solved problem, and one of the solutions which we ultimately chose to adopt is the channels system from the Phoenix framework in Elixir. What drew us to Phoenix was the scalability and reliability of the server side, and the ability to have server-side business logic working with the real-time data in the same service. The underlying BEAM virtual machine allows each connected client to have its own process with strong isolation, so even if something goes unexpectedly wrong with that client connection and the process crashes, the overall server continues running and simply restarts the process. It can also handle thousands of these processes in a single instance.

The channels protocol allows us to multiplex a number of streams (”channels”) onto the same WebSocket connection, handles joining and leaving channels, message acknowledgment (and request/reply semantics), and also supports regular heartbeats to keep the connection alive.

We only use Phoenix and the channels as a transport, the diff protocol described above is opaque to it, and the diff-applying logic is built in Rust, reusing the same code the clients use to apply and rebase diffs thanks to rustler.

Building the client

With Phoenix selected as the messaging infrastructure, we had another decision to make. There is an official client available for JS and unofficial ones for Kotlin and Swift. We could simply use those and build the Crux capability to interface with them at the level of the Phoenix channel operations. However, that would be going against our general strategy of reducing the number of implementations involved in the realtime collaboration systems. We also needed the ability to test the system thoroughly, including injecting all kinds of failures to make sure we recover correctly (more on that later).

Ultimately, we decided that we will build our own Phoenix channel client, in Rust, following the Sans I/O model of Crux capabilities. In fact, we’d do it from WebSockets up.

We mentioned Crux capabilities before, but didn’t yet talk about what using them typically looks like. Here’s a simple example of using one of our custom ones, bridging to our authentication handling on the app side:

Authentication::get_auth_token().then_send(Event::AuthorizedGetComments)This call returns a Command, which is then returned to Crux to handle (for a reminder of how this works, you can read the second part of this series).

This works fine for one-off calls with a response, but with the channels client, there is session state involved. We needed an API which would allow the engine modules to join channels, subscribe to messages and send messages. In the background, the client should transparently handle connection issues, retry sending messages on timeout, implement an exponential backoff on reconnect attempts, etc.

async to the rescue

While the basic capability APIs don’t require it, Crux allows the effect handling code to be written in async Rust, and we leant heavily into this. We adopted a pattern, which allowed us to have a number of concurrent “processes” managing phoenix channel sessions, a phoenix socket connection and the underlying WebSocket, each with a companion instance with a public API given to the business logic, acting as a “remote control”. In each case, the two halves would share a “port” - a pair of async channels used as a communication and synchronisation mechanism between the business logic and this background process.

As an example, here’s a heavily abridged version of the connect method on the socket:

fn connect<Config, Effect, Event>(

&mut self,

url: &Url,

connection_parameters: Option<&Config>,

heartbeat_interval: Option<Duration>,

reconnect_delay: Option<Duration>,

) -> crux_core::Command<Effect, Event>

where

Config: Serialize + Debug + Clone,

Effect: Send + From<Request<TimeRequest>> + From<Request<WebSocketOperation>> + 'static,

Event: Send + 'static,

{

crux_core::Command::new(|ctx| {

// ...

async move {

let websocket_stream = WebSocket::connect(connection_id.clone(), full_url).into_stream(ctx.clone());

let commands_stream = inner_port.commands_stream().fuse();

let mut heartbeater = Heartbeater::new(connection_id.clone(), ctx.clone());

let mut reconnecter = Reconnecter::new(connection_id.clone(), ctx.clone(), reconnect_delay);

let heartbeat_timer = Time::notify_after(heartbeat_interval.into()).0.into_future(ctx.clone()).fuse();

// ...

while !disconnected {

futures::select! {

event = websocket_stream.next() => {

// ... handle event from websocket

// including a disconnect, handled by the reconnecter

// and heartbeat messages, handled by the heartbeater

},

command = commands_stream.next() => {

match command {

// ... handle command, which can be one of

// Send, GetStatus, Reconnect or Disconnect

}

},

_ = heartbeat_timer => {

heartbeater.on_timer_notification().await;

heartbeat_timer.set(Time::notify_after(heartbeat_interval.into()).0.into_future(ctx.clone()).fuse());

}

}

}

}

})

}We’ve omitted a lot of the nitty gritty of the setup, but the key building blocks are there. The main things to note are:

The function returns a

Commandwhich expects theEffecttype to support time requests and web socket operations - those are the interactions with the native side of the app we need for thiscrux_core::Command::newexpects a closure which returns a future, which Crux will keep polling for usThe returned Future does some initialization and then enters a

whileloop which runs until the socket is disconnectedIn the while loop, we use

futures::select!to handle one of three possible incoming items: an event on a subscription to the underlying WebSocket, a command, coming from the socket instance held by the core business logic, or a heartbeat timer firing

These are all Rust futures or streams created either by an async channel (in the case of commands_stream), or by the underlying WebSocket and Time capabilities (they get converted into futures and streams using the into_* methods, which expect the ctx provided by the outer closure. That allows them to communicate to the native side of the app).

We used a similar pattern with a long-running future and a remote control for handling a channel session (started with join).

This then allows the realtime business logic to use a simple high-level API like this:

let (join_command, mut channel) = socket.join(

project_editing_channel_topic(id),

ChannelOptions {

// ...

},

);

channel.on_server_event(DIFFS_EVENT, move |payload| {

Event::ReceivedRealtimeSyncFromPeer { id, payload }

});

channel.on_server_event(PROJECT_EVENT, move |payload| {

Event::ReceivedRealtimeProject { id, payload }

});

Both the socket and the channel in the example above have an associated long-running future in the Crux effect runtime handling the mechanics of the connection.

You can see that the Phoenix client implementation uses async Rust heavily, and the code doesn’t look very different from what you’d expect async Rust code to look like, but there is one key difference: all the I/O bottoms out in futures returned by Crux capabilities, futures which just express the intent (e.g. to send a message to a socket or to subscribe to listening on a socket). The entire Phoenix client is “Sans I/O”, hosted on the WebSocket and Time capabilities.

This enabled really thorough testing of our implementation. The tests effectively stand on both sides of the client: the core facing public API and the WebSocket and time primitives, which lets us manipulate the socket behaviour and time ad-hoc, without setting up any kind of stand-ins.

Testing the realtime collaboration

When it comes to realtime collaboration, there are several layers of testing necessary. If the idea of a testing pyramid applies anywhere, it’s here.

First, we need to make sure the basic features of the client work correctly. Then we need to make sure the business logic on top of it works correctly. We also need to ensure the end to end integrates together right, and there is more...

Let’s start with the basics though. As an example, here’s a test checking that request timeouts work as expected:

#[test_log::test]

fn request_timeout() {

let mut app = RealtimeTester::new(App::default());

let mut model = Model::default();

let _ = app.join("channel:test", &mut model);

let timeout_duration = Duration::from_millis(91729387129);

let update = app.update(

Event::Request {

event_name: "get_thing".to_string(),

payload: Some(payload("thing_payload")),

timeout: Some(timeout_duration),

},

&mut model,

);

let send_effect = find_send(update.into_effects());

let (update, _) = app.assert_send_and_confirm(send_effect);

let mut timeout_request = find_request_timeout(timeout_duration, update.into_effects())

.expect("expected time request");

let TimeRequest::NotifyAfter { id: timer_id, .. } = timeout_request.operation else {

panic!("Request should be NotifiyAfter");

};

let update = app.resolve(

&mut timeout_request,

TimeResponse::DurationElapsed { id: timer_id },

);

app.apply_all_updates(update, &mut model);

assert_eq!(model.received, vec!["timeout"]);

}The RealtimeTester is a test helper giving us a slightly higher-level API to send the right event and service common effects (for example, RealtimeTester::join joins a channel and makes sure the expected effect requests have happened).

In the test itself, we start a Phoenix request message to "get_thing", we confirm the send, but instead of then delivering the response from the service, we first trigger the timeout, as if the request took too long to process. We can then make sure that it resulted in the right outcome in the model.

This test is written against a one-off test app with very simple and predictable behavior, as its designed to test the client implementation in isolation.

Because there is no actual clock involved, this test runs in 56 ms. In fact, all the basic tests covering the client implementation run in 73 ms, because they execute concurrently.

❯ cargo nextest run phoenix_channels

Finished `test` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.79s

────────────

Nextest run ID 3eaf616b-393e-4942-896e-e52de795d9a1 with nextest profile: default

Starting 12 tests across 1 binary (412 tests skipped)

PASS [ 0.034s] phoenix_channels::message::tests::test_message_from_wire

PASS [ 0.035s] phoenix_channels::presence::tests::test_deserialize_diff_payload

PASS [ 0.037s] phoenix_channels::message::tests::test_message_to_wire

PASS [ 0.037s] phoenix_channels::presence::tests::test_deserialize_state_payload

PASS [ 0.051s] phoenix_channels::tests::joins_and_leaves_a_channel

PASS [ 0.052s] phoenix_channels::tests::buffers_and_sends_messages_until_reconnected

PASS [ 0.052s] phoenix_channels::tests::buffers_and_sends_messages_until_connected

PASS [ 0.053s] phoenix_channels::tests::message_subscription_and_filtering

PASS [ 0.032s] phoenix_channels::tests::receives_presence_updates

PASS [ 0.031s] phoenix_channels::tests::request_response

PASS [ 0.032s] phoenix_channels::tests::request_timeout

PASS [ 0.032s] phoenix_channels::tests::resets_connection_when_server_doesnt_reply_to_heartbeat

────────────

Summary [ 0.073s] 12 tests run: 12 passed, 412 skippedThere are similar tests for the actual logic of the realtime protocol, and tests for entire basic user journeys from opening a project through some edits to leaving again. We also have tests checking full round-trip use from TypeScript and Swift. But even that is not quite enough.

It’s not the problems we know about, reproduce and can test for, which we need to worry about. It’s all the random ones we don’t know about, caused by ordering of messages, and connection problems.

Data races?

While we got to a working implementation of realtime collaboration, starting with presence, fairly quickly (in a matter of weeks), we knew getting it to the level of quality required for production will take longer.

We needed to ensure that all the code involved in the realtime collaboration is rock solid, and immune to all the possible races and failures, and all the various orders they might happen in. To do that, and to discover all of the possible failure scenarios, we built a custom testing harness for the realtime collaboration, which we dubbed the Fuzzy Tester.

The job of the Fuzzy Tester was to set up a collaborative editing session with multiple clients, generate randomised edits they all perform, execute them (potentially injecting failures) and at the end verify that all the clients converged - ended up with the same document. It can run the same tests using an actual network connection or without it, handing WebSocket messages over manually, which allows various delays and disconnects to be injected. The randomisation is based on a pseudorandom number generator, and whenever a failure is found, the seed is reported, so that the problem can be investigated and fixed.

The realtime Fuzzy Tester was in fact not the only randomized testing tool we wrote for the growing engine, and the technique deserves a deeper discussion, so that’s what we’re going to look at in the next and final post in this series – the testing of the Photoroom engine.

Realtime collaboration is now live

It’s been more than 18 months since we embarked on this journey: this blog series is a reflection on the choices we made, the lessons we learned and the path we took. It is a genuine pleasure to announce that we now have reached a confidence level in our implementation such that we have rolled out live collaboration in Photoroom to 100% of our users regardless of the platform they use. Our Android users now have a full Compose-based editor, where they get to see, in real time, what their teammates on iOS using a full SwiftUI-based editor are doing, and vice-versa. I am so incredibly proud to have been a part of this journey, but I have to admit this is still just the beginning. The Photoroom engine is poised to encompass more and more of our collaboration features (Team spaces, Brand Kit, Sharing, etc), a lot of those being destined to become real-time at some point. There is still a lot of work to be done, and we would love to speak with anyone who followed along this journey. If this sort of work sounds exciting to you, we’re hiring a head of cross-platform to provide a seamless experience to millions of users. Learn more here.