Building live collaboration in Rust for millions of users, part 5

Automated testing and fuzz testing

Last time, we left off with a sketch of the testing tool to discover various data races and similar issues in the implementation of realtime collaboration. Today we’ll look at the detail of how we did this and other testing of the Photoroom engine.

Quality bar is higher in the engine

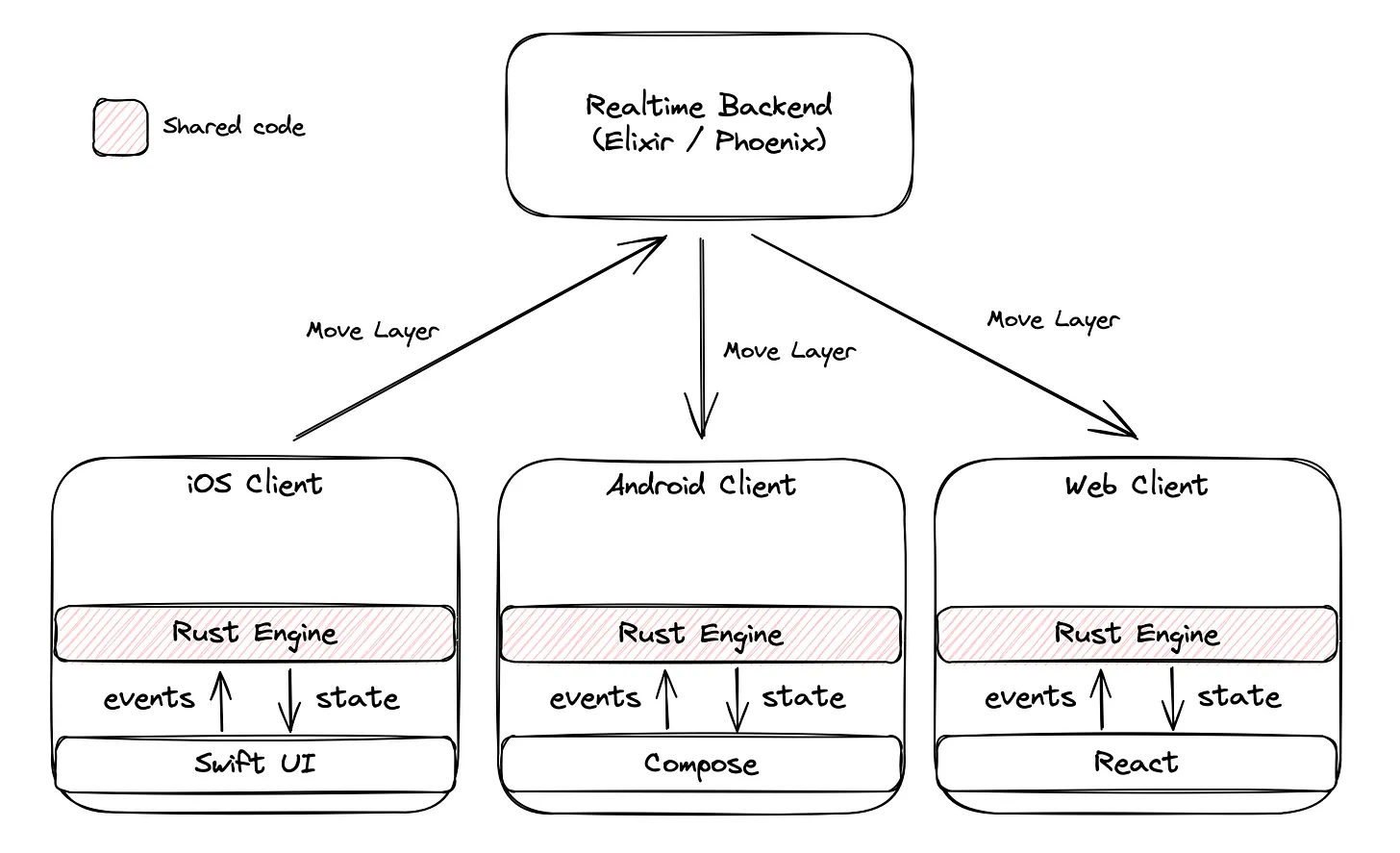

When we set out to move the key user features of Photoroom into the engine, we were doings so with the goal of consistency, and maintaining just one implementation. This implicitly raises the quality bar for the engine, because a bug in it can affect all three platforms at once. We knew we needed very high levels of automated testing to get ourselves as close to proving the engine does exactly what its supposed to, before we let the apps use the logic. (That still leaves all the things which work exactly as intended, but for which the intention is incorrect, but we wanted to at least eliminate all the rest).

With Rust, we had a good foundation. The strict static analysis rarely lets one get away with unintentional behaviors, and the runtime speed makes unit tests extremely fast. But as we said at the outset, it’s not just pure logic we need to test, it’s entire user journeys, complete with state changes and I/O.

Thankfully, our model makes this just as fast as unit tests, because of the Sans I/O approach with managed effects. We’d need to make sure that all the effects handling is implemented correctly across the three platforms, but once in place, we could test the engine in isolation – just the business logic.

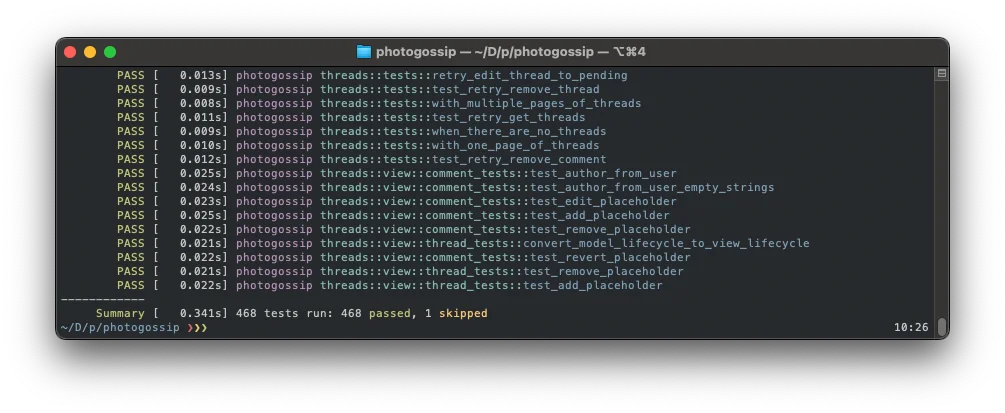

At the time of this writing of the 1325 tests in the Rust part of Photoroom engine, 468 are testing the Crux based portion of it. Despite running tests like show_all_will_fetch_first_page_and_last_opened_on_first_call_and_do_nothing_on_second_call, and revert_add_comment_that_is_completed, which run full user interaction sequences, including API service calls, timers, storing values in local storage, etc., and check that what ends up in the view model is correct, they run in less than 400ms. The entire Rust test suite for the engine runs in 1 second when omitting rendering snapshot tests (25 seconds when those are included) and that is starting to feel slightly on the slow side.

An example test

To give you a sense of what the tests are like, let’s look at one example:

#[test]

fn test_create_then_fetch_uploaded_images() {

let app = TestApp::new();

let mut model = logged_in_model();

let image_id_1 = UploadedImageId::new();

let image_1 = Box::new(ImageUpload {

id: Some(image_id_1),

image_uri: "gs://image-path".parse().unwrap(),

mask: None,

width: 100,

height: 100,

});

let uploaded_image_1 = uploaded_image_with_id(image_id_1);

let update = app.update(

Event::CreateUploadedImage { image: image_1 }.into(),

&mut model,

);

let mut http = app.provide_auth_token_expect_effect(update).expect_http();

let response = HttpResponse::ok().json(uploaded_image_1.clone()).build();

app.resolve_to_event_then_update(&mut http, HttpResult::Ok(response), &mut model)

.assert_empty();

assert_eq!(model.view().uploaded_images.images.len(), 1);

let update = app.update(Event::BeginFetchUploadedImages {}.into(), &mut model);

let mut http = app.provide_auth_token_expect_effect(update).expect_http();

let page = Page {

count: 1,

next: None,

previous: None,

results: vec![uploaded_image_1],

};

let response = HttpResponse::ok().json(page).build();

app.resolve_to_event_then_update(&mut http, HttpResult::Ok(response), &mut model)

.assert_empty();

assert_eq!(model.view().uploaded_images.images.len(), 1);

let image_id_2 = UploadedImageId::new();

let image_2 = Box::new(ImageUpload {

id: Some(image_id_2),

image_uri: "gs://image-path".parse().unwrap(),

mask: None,

width: 100,

height: 100,

});

let uploaded_image_2 = uploaded_image_with_id(image_id_2);

let update = app.update(

Event::CreateUploadedImage { image: image_2 }.into(),

&mut model,

);

let mut http = app.provide_auth_token_expect_effect(update).expect_http();

let response = HttpResponse::ok().json(uploaded_image_2).build();

app.resolve_to_event_then_update(&mut http, HttpResult::Ok(response), &mut model)

.assert_empty();

assert_eq!(

model

.view()

.uploaded_images

.images

.iter()

.map(|i| i.id)

.collect::<Vec<_>>(),

vec![image_id_2, image_id_1]

);

}This checks that creating an image upload sends the right HTTP requests and updates the view model optimistically along the way:

First it creates an image with

Event::CreateUploadedImageThe app (the engine module being tested) returns an

updatewhich has the immediate effects and events emitted from theCommandreturnedThe test provides an auth token and expects a HTTP effect

Then it creates a response (a 200 OK) to resolve the effect request with, and checks there’s nothing further from the app.

The user should also see the uploaded image in a view model

Next, the test starts a fetch of uploaded images, and goes through a similar loop, returning just the one image we just “uploaded”. We should not see the image duplicated at this point - it’s the same image

Finally, the test runs one more image upload and makes sure that both images are present and in the correct order

This is a reasonably small test, but you can see how testing of I/O works without any I/O actually happening. The I/O testing is opt-in - we only handle the effects we’re interested in and ignore the rest, and we don’t need to explicitly disable those in any way.

Beyond expectations

There are two big features of the engine, for which this type of testing wasn’t quite enough. The problem is that tests like this only cover scenarios that engineers can think of. But these two had a lot of scenarios which engineers are particularly bad at thinking of: race conditions.

The two features in questions both have to do with collaboration. The first one is the original document synchronisation (”sync”), the second is the realtime system. We ended up going for a similar strategy with both of those, but lets look at them separately.

Sync

Team collaboration support has been in Photoroom for a long time before realtime features. Our users expect to be able to work on their documents as if they are local, and have them seamlessly save in the cloud, available on other devices and visible to their teammates. To support this on top of a simple REST API requires the apps to do quite a lot of work to make sure work is never lost, even if network connection isn’t quite as reliable as we’d like.

In broad strokes, every edit made is stored locally and submitted to the API, meanwhile the user can continue editing the document. If for whatever reason committing to the API didn’t work, we always have the local copy and can resubmit it at an opportune moment. Additionally, in order not to overload the API, we need to throttle the commits to a reasonable rate, which we do using debounce timers, and, where possible, newer edits supersede older edits which have not been submitted yet.

Reading this, you can probably imagine the state machine, and the minefield of data races which can occur, and how hard we need to work to do the correct thing in every situation. It is exactly the kind of thing which humans are very bad at imagining, and which is full of unlikely edge cases which will definitely occur in production at the scale Photoroom operates on. There are two problems:

Writing all those test scenarios

Thinking of all of them

While the number of possible scenarios is astronomical, there are only a few actions and possible problems which the scenarios are made up of. The really hard part is timing, or more specifically, ordering in which things happen. Rather than trying to think of all the possibilities, why don’t we randomly generate them?

Deterministic simulation testing

Since the Photoroom engine is a Crux app, it has a very stable interface we can rely on. What we need to be able to do is as follows:

Generate a plausible event

Sufficiently replicate the REST API, with the ability to inject failures of various types

Introduce randomness, but in a repeatable way

If we repeatedly generate a plausible event and service all the effects the engine is requesting, we can exercise the state handling in all the ways it should be able to handle. Every step of the way we can either generate a new user input, or process one of the pending effects.

It may sound like implementing a replica of all the effects is too much work to be worth it, but in our case, it only ended up being roughly 500 lines of code (built up over time, as we introduced more and more devious ways for the outside world to get us).

The real value of this approach is in the randomisation. There are a number of things we should randomise, to prove we are immune to them:

the chance of introducing a new event while effects are still being processed

the order in which effects are being processed and outcomes delivered

for the more interesting effects, their outcomes (e.g. an occasional 500 from the API server)

The key to the randomisation being useful, is to rely a pseudorandom number generator with a known seed, so that when a particular run fails, the seed can be captured, and the run repeated and investigated. This has limitation, in that any changes to the fuzz test code which introduce an additional “dice roll” change the meaning of the seeds.

The remaining question is “what should we look for?”. This is probably one of the trickier things about this testing approach. Not every domain has good “invariants” - things which should always stay true, no matter what happens in the system. Here’s a few examples of ours:

The POST endpoint should never receive a request with a document that already exist

PATH and PUT endpoints should never receive requests for document which don’t exist (either yet, or any more)

The contents of the documents should never move “backwards”, losing the user’s work (we keep track of the revisions and base revisions as edits are made)

These are quite simple and common sense, but they were sufficient to catch quite a lot of very subtle race conditions, where if things happened in just the right order, work would be lost.

Here is the key loop of the tester, with a bunch of details removed for clarity:

fn run(&mut self, num_inputs: u8) {

self.fixtures = self.project_fixtures(100);

self.caps.http.set_fixtures(&self.fixtures);

let mut remaining_inputs = num_inputs;

while self.has_more_work_to_do(remaining_inputs) {

if self.rng.gen_bool(0.005) {

// 1-in-200 chance of resetting state

self.reset_client_state();

continue;

}

// Either generate a user input, or take a step off the buffer

let Step { step } = if remaining_inputs > 0

&& (self.step_buffer.is_empty() || self.rng.gen_bool(0.2))

{

remaining_inputs -= 1;

let next_event = self.generate_plausible_event();

self.stats.add_event(next_event.clone());

Step {

step: Update::Event(next_event),

breadcrumbs: Breadcrumbs::new(num_inputs - remaining_inputs),

}

} else {

let step_idx = self.rng.gen_range(0..(self.step_buffer.len()));

self.step_buffer.remove(step_idx)

};

let mut update = match step {

Update::Event(event) => {

assert_model_is_self_consistent(

&self.model,

"Model inconsistent before update",

);

let update = self.app.update(event, &mut self.model);

assert_model_is_self_consistent(&self.model, "Model inconsistent after update");

update

}

Update::Effect(response) => {

match response {

EffectResponse::Authentication(mut req, res) => self

.app

.resolve(&mut req, res)

.expect("Auth request should resolve"),

// ... other effects

}

}

};

let num_evs = update.events.len();

for (ix, event) in std::mem::take(&mut update.events).into_iter().enumerate() {

let step = Step {

step: Update::Event(event),

breadcrumbs,

};

self.step_buffer.push(step)

}

for (ix, effect) in update.into_effects().enumerate() {

if let Some(response) = self.resolve_effect(effect) {

let step = Step {

step: Update::Effect(response),

breadcrumbs,

};

self.step_buffer.push(step);

}

}

}

}Notice the various calls to self.rng – this is the pseudorandom number generator introducing randomness to the tests. We use it to randomly pick from the queue of steps to process, to generate the plausible events, to randomly pick times at which we introduce additional user inputs, and we also pass it to the fake effect implementations (behind self.resolve_effect), so that they can randomise their behaviour too.

As with unit and journey tests above, the Sans I/O architecture shines here as well. With the later versions of this testing harness which runs tests concurrently we can run around 3000 random scenarios a second, well over a 100000 tests a minute. As I write these lines, they complete with no failures.

Realtime collaboration

With the introduction of realtime collaboration, this testing approach gained a dimension - the collaborators. What we wanted was a randomised simulation of a group editing session, proving that no matter what happens, all the peers eventually end up with the same exact version of the document. This simplified the invariant (at the end of the run, we compare the documents) but complicated the testing harness slightly: we wanted to be able to test both with simulated network controlled by the testing harness, and real network, with the real Phoenix server behind it. This resulted in another version of the tool, nicknamed Fuzzy Tester.

The sync fuzz tests ran inside a unit test run – we execute them with cargo test, and they are part of the main target. Fuzzy Tester is a standalone CLI tool. Each approach has merits, but fundamentally they both work in very similar ways – they bring their own implementations of the relevant I/O, create an instance (or several instances!) of the engine and generate a large number of user inputs with randomisation. Then they execute them, with delays and drops, looking for any any broken invariants.

Where the sync fuzz tests only ran a deterministic (but pseudorandom) simulation of the API backend, the Fuzzy Tester supports two modes - deterministic and end-to-end. The deterministic mode runs all in a single process, creates a number of instances of the engine and a realtime server simulation, then runs a randomise sequence of edits in each instance and passes the requested messages to the server and back with a network simulator which can drop and hold messages and cause all kinds of havoc. The end to end mode starts an actual Phoenix server and run the simulation against that, over a local network. Both modes have lots of options to control how the simulation exercises the logic to look for different kinds of issues. This way, we can exercise the engine code in many different scenarios, making sure there are no logic failures leading to clients getting out of sync.

A short Fuzzy Tester run with ten collaborators in deterministic mode with failure injection runs in every CI build, to spot any problems we may have introduced with the latest changes. It saved our bacon on many occasions.

The missing layer of the testing pyramid

We believe that this testing approach, together with how easy, fast and reliable its made by the event-driven, Sans I/O architecture of the engine, has saved us huge amounts of time finding and fixing bugs before releasing the realtime collaboration, and just as large a number of production incidents we didn’t ever have to handle. Of course we still had a few bugs which even this amount of testing didn’t find, but with the number of problems we caught beforehand, we’re convinced it would’ve been a lot worse, if it wasn’t for the simulation testing.

Alongside basic unit tests, unit tests through the engine language bindings (Swift, Kotlin, TypeScript), end to end tests in our engine demo apps, and full end to end tests of the fully integrated apps, the different testing layers give us significant confidence that Photoroom works when they pass. On the engine side, it takes about 10 minutes to build and run all of them on CI (and there are thousands at this point), and just seconds to run the Rust-side test suite – fast enough to run every time the Rust code compiles.

It is in large part this extensive and cheap test suite that allowed us to continue to evolve the engine as fast as we have, iterate on our approach to fundamental developer infrastructure, and deliver new features and changes as quickly as we have. Crucially, even 18 months since we started bringing significant portions of Photoorom’s business logic into the engine, we don’t feel any significant loss of speed of iteration, or drop in quality, on the contrary. The foundations are strong, and we expect to build on them for years to come. If this sort of work sounds exciting to you, we’re hiring a head of cross-platform to provide a seamless experience to millions of users. Learn more here.