Understanding feature flags: The foundation of reliable A/B tests

In my first article, I explained why sequential testing is the right methodology for experiments at Photoroom.

Before adopting it, we spent months digging into the underlying mechanics of experimentation - reading documentation, testing edge cases, and comparing practices with other teams.

We learnt what feature flags actually are, and how they power the entire experimentation flow. We broke down every concept - assignments, variants, deployments, exposures - and trained our internal teams on why each of them plays a critical role in producing trustworthy experiment results.

This article aims at sharing our learnings and our internal recommendations when setting up a flag.

1. Feature flags: The hidden engine of product velocity

Feature flags control whether a specific feature or functionality is active or inactive in the product. At Photoroom, feature flags have always been part of how we build. They let us control which version of a feature a user sees without redeploying code each time, which perfectly supports our #shipfast culture. With a single configuration change, we can adjust the app’s behavior for targeted users in seconds.

We rely on feature flags across many areas of the product:

Onboarding: continuously testing which questions help new users understand the value of Photoroom without overwhelming them.

Paywalls: essential during recent pricing evolutions where we needed high control and low risk.

Machine learning models: every new model from the ML team is tested instantly on a small portion of users to measure uplift.

For growth topics: we send conversion values back to the networks through flags.

We can use the same flags many times whenever we need to test a new version.

Our naming convention for feature flags name and key:

{platform}_{linearticket}_{object}

We use feature flags so extensively that we currently have around 460 active flags. Some of them likely shouldn’t be active anymore: the risk of legacy variants, stale configurations or inconsistent behavior grows quickly. A topic we’ll explore in another article 👀.

What wasn’t clear to many of us (myself included) was how feature flags connect to experimentation. The answer is simple: feature flags are the foundations of the experimentation system. In other words, all experimentations use feature flags but not all feature flags are for experimentation purposes. Every experiment is created on top of a feature flag, which determines which population sees variant A vs variant B.

This relationship isn’t obvious in Amplitude’s UI, where experiments and flags are presented side by side as if they were independent. This often leads to the misconception that they are separate systems - while in reality, every experiment is powered by a feature flag behind the scenes. Amplitude confirmed that a clearer separation is coming (rumored for Q1 2026!).

2. Variants: one feature flag, multiple product realities

Once you understand that feature flags sit at the core of every experiment, the next concept to master is the variant. A single feature flag can control several different versions of the same feature: each one representing a different “reality” the user might experience.

Let’s say we want to test a new version of our ML models. At Photoroom, we have a powerful tool called AI Backgrounds that enables you to generate realistic backgrounds with AI, starting from a prompt or inspiration image. Our ML team is constantly working on fine tuning our models and when one is ready, we like testing it to measure potential uplift in the conversion image generated > export.

If we were to test 2 different models on iOS users, depending on their subscription type, there will then be 3 variants: Variant A will be the first new version; Variant B the other new version, and “control” will be the current experience every user has.

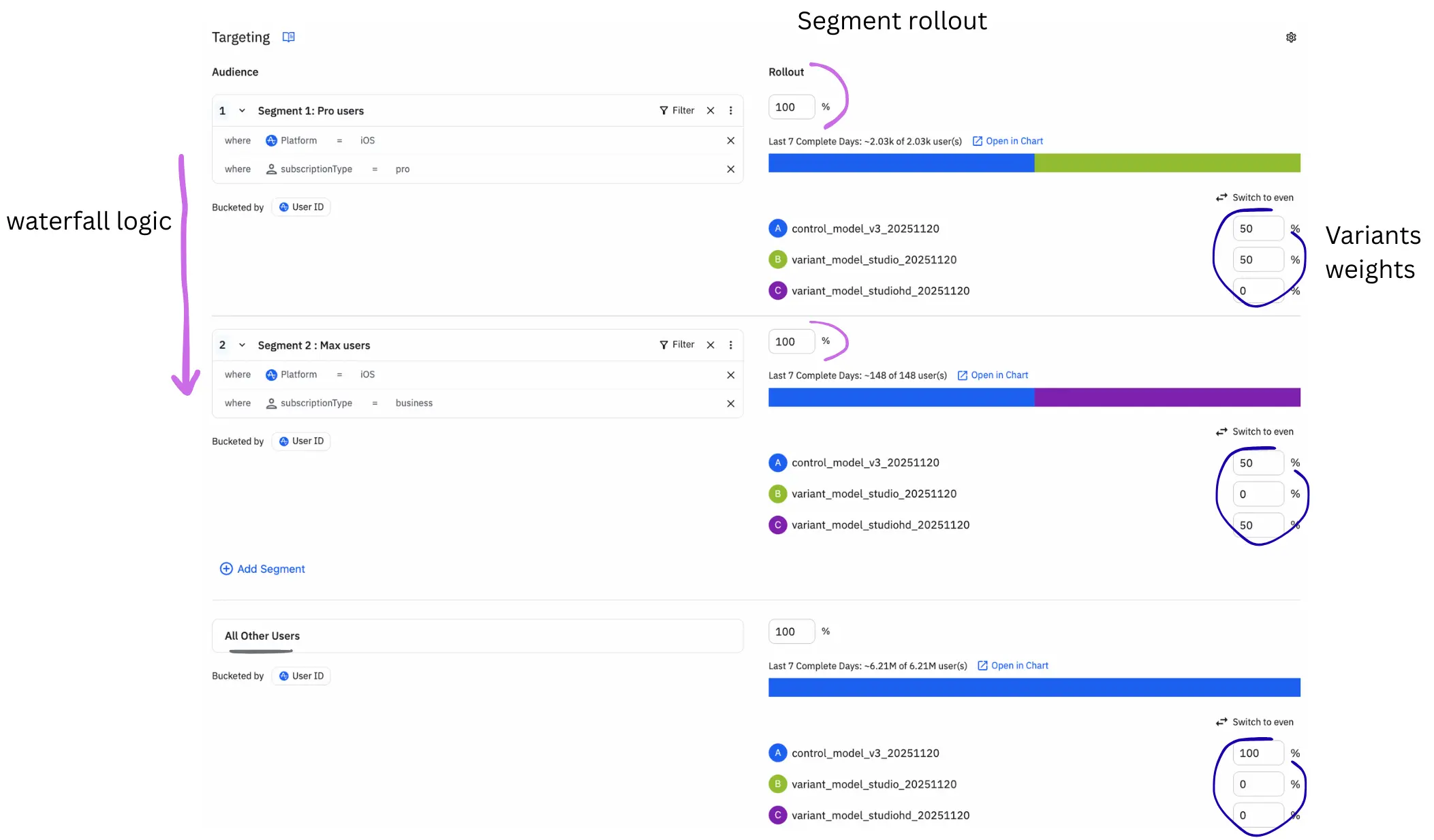

To limit the test to iOS new users per subscription, we will then need to create different segments of users within the flag. A segment is a set of filtering conditions (rules) that determines which users are eligible to be evaluated by a feature flag. Segments restrict the population: only users who satisfy the segment rules can enter the flag and receive a variant.

Segments can:

filter the population → who can be exposed

check user properties (country, platform, device, subscription…)

check behavioral conditions with cohorts (opened app x times, made x+ exports…)

check technical conditions (OS version, build number…)

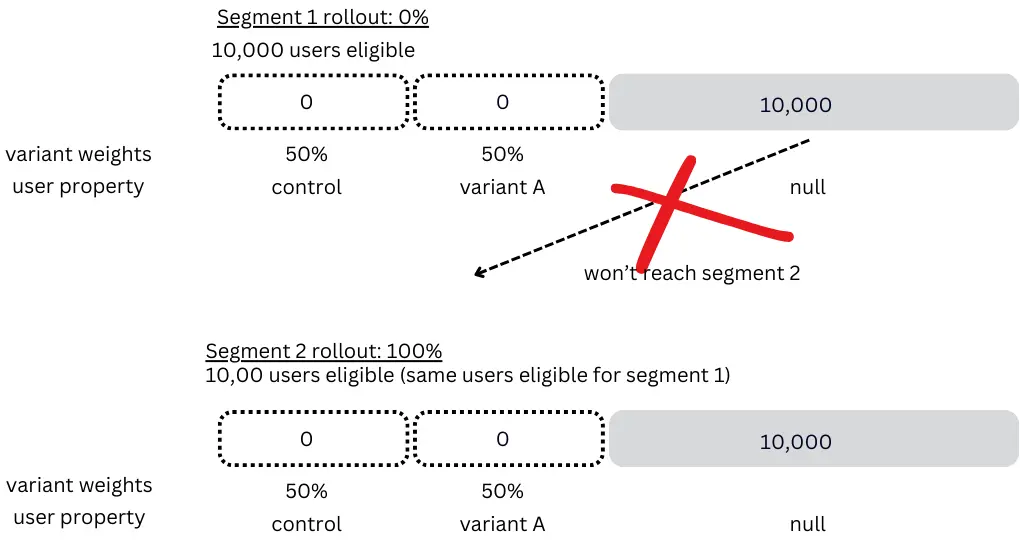

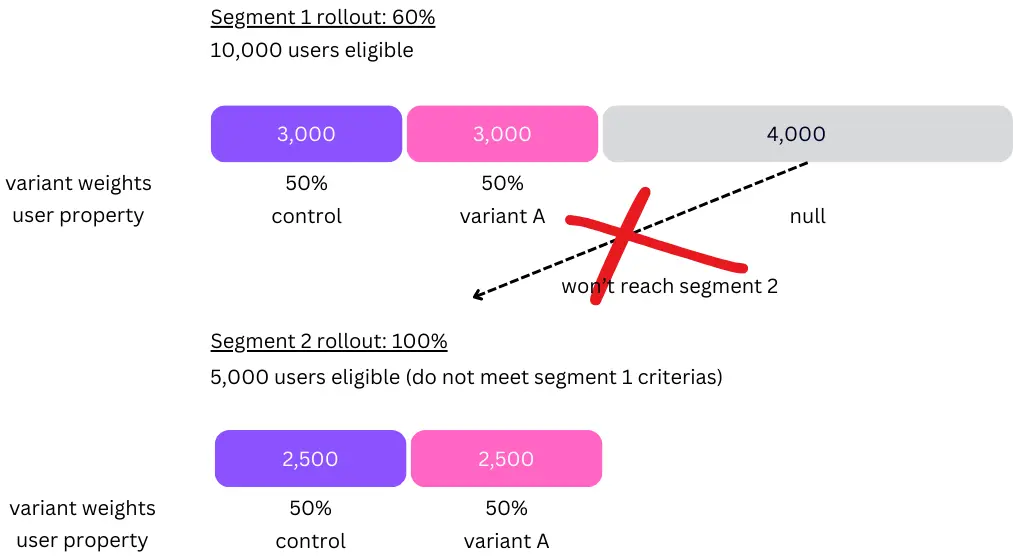

Important to keep in mind that segments follow a vertical waterfall logic from top to bottom (see in the chart below): users will fall in segment 2 IF and only IF they are not eligible to segment 1.

At Photoroom, it happened that we made the following mistake: we had set the first segment rollout to 0% as we did not need it anymore, but we did not realize that most users were eligible for it and therefore no users went down the funnel! We now have implemented observability for segment rollout percentages.

Segment eligibility always takes priority over waterfall progression

Keep in mind to always have someone check in the code base that having a null value for the property will have the correct behavior, i.e a user will see the normal onboarding version.

Variants force us to be explicit about what each user segment should see. Good naming helps a lot. At Photoroom, we introduced the following naming convention for variants: {variant_type}_{short_description}_{versionning}_{yyyymmdd}

e.g: control_onboarding_20251102 and variant_onboarding_v3_20251102

It seems a little wordy but it makes debugging easier (reminder we have 400+ active flags) and it keeps experiment analysis clean, especially when dozens of tests run simultaneously.

3. Feature flag: for who? Understanding assignments

User property

An assignment is the moment a user is attributed to a specific variant - control or treatment - for a given feature flag. Once assigned, the user receives a user property whose key is the flag name and whose value is the variant. In our example, the user properties would be:

ios_2855_mlmodels = control_model_v3_20251120 ,variant_model_studio_20251120 or variant_model_studiohd_20251120 for variants A,B and C.

As soon as a user qualifies, Amplitude determines their variant when the SDK evaluates the experiment - meaning during fetch() calls or evaluate() on the server side. This is universal: evaluation is what triggers assignment. The assignment is fully deterministic - meaning that as long as the inputs to the hash function (bucketing key, bucketing salt, bucketing unit, variant weights, and any relevant user properties) remain unchanged, the user will consistently receive the same variant every time the experiment is evaluated.

At Photoroom, we decided to trigger assignment at each app open.

In practice:

For our example, each time a user opens our app, an assignment is triggered. If the user meets the iOS and subscription type criteria, the system evaluates the flag and assigns either control, variant A or B. From that point on, the user keeps that assignment as a user property. All users who don’t get assigned to a variant will have their user property set to “null”

Deployment

In this example, the test runs on iOS, but that doesn’t necessarily mean the deployment is iOS.

Deployment defines where evaluation happens - and therefore which system performs the assignment.

If the backend fetches the variant for the iOS app → deployment = backend

If the iOS SDK fetches the variant → deployment = iOS

Our example compares ML models, and at Photoroom, we prefer backend deployments whenever possible (especially for ML model experiments), even when the experiment is only visible on one platform. This ensures the work is done once rather than on every platform, and it makes code more complicated to hack. Client-side deployments remain useful when the client needs to directly evaluate flags.

Deployment matters because it defines where the source of truth lives for assignment - a key point when debugging exposure inconsistencies.

Bucketing key

To assign users in a deterministic way, Amplitude needs a bucketing key: a stable identifier that ensures the same user always lands in the same variant. A stable bucketing key also ensures fairness: users are evenly distributed according to the variant weights, without accidental bias such as device resets or reinstalls.

We recommend:

user_id (id tied to the user across all tools) for mobile apps (more stable, fewer variant jumps than using the Amplitude ID)

device_id for web

The bucketing key ensures that the same user always hashes to the same bucket.

Hash function

The hash function is what makes assignment deterministic.

Why do we need deterministic assignments?

Because once a user is assigned to a variant, they must consistently receive the same variant for the entire duration of the experiment or feature flag. Determinism guarantees that the assignment is stable and reproducible across sessions and devices. Without it, users could switch variants mid-experiment, which instantly invalidates the results and makes the test impossible to analyze.

Amplitude uses a different hash seed (bucketing salt) for every flag or experiment.

This avoids cross-flag correlation — otherwise the same users could consistently fall into the same variants across multiple flags, which would bias results and create unwanted behavioral patterns.

Given the same inputs which are the flag key, bucketing key, bucketing salt, the algorithm always produces the same output: 100% of the time, with no randomness.

bucketing_key → stable user identifier

flag_key → unique key of the feature flag or experiment

salt → project-specific, managed by Amplitude

Sticky bucketing

Sticky bucketing is an option offered by Amplitude and it ensures that once a user has been assigned to a variant, the experiment will always return that same variant on every evaluation. Instead of recomputing the hash each time the app opens - which could lead to variant switches when rollout percentages change - Amplitude stores the assignment and reuses it for the rest of the experiment. Sticky bucketing prevents “variant jumping” and guarantees a stable user experience, but it does not prevent earlier assigned users from appearing later in the analysis if your exposure event is repeatable.

Testing

A very important part of the setup of our tests is selecting the right testers. At Photoroom, we value dog fooding, which means that everyone in the company regardless of their job, is expected to test the app and its new features on the test version. The guideline is that every employee should be added in a treatment group so that we are all aware of what’s about to be shipped (we add the cohort that contains every employee). Ideally, the person setting up the flag would add their own user_id as testers for each variant to make sure the flag behaves as expected.

Exposure

Exposure is the moment a user becomes part of an experiment - it’s the event you track to indicate that the experiment actually was seen by them. It tells Amplitude when a user entered the test, so results can be calculated correctly. Exposure can be single-shot or repeatable depending on how your product is instrumented. If exposure is too early, too late, or tied to the wrong event, experiment results will be biased.

Feature flags may look like a simple configuration layer, but they’re actually the foundation that makes reliable A/B testing possible. They decide who sees what, when, and where. Without a solid understanding of how segments, rollouts, assignments, and exposures work together, even the most sophisticated experiment methodology breaks down. This is why we started our experimentation series with the “why” in the first article on sequential testing, before moving into the “how” with feature flags.

This article is the second chapter of a broader series on how we run data-driven experimentation at Photoroom. The next ones will cover exposure design, progressive rollouts, and experiments results charts.

Thanks for reading! If you have questions, want us to cover a specific topic, or simply disagree with something (always welcome!), feel free to reach out on LinkedIn/X - I’d love to continue the conversation.

And if you’re interested in joining Photoroom, take a look at our open positions.

Keep reading

Sell faster with studio‑quality product visuals

Drive sales with professional visuals you can create in minutes, with brand consistency and control.