The road to live-collaboration, part 1

Photoroom’s approach to cross-platform code

At Photoroom, we are no strangers to cross-platform development. Since our early days, we have capitalized on building cross-platform code to help us move fast and ensure that Phororoom looks and feels the same wherever you use it: the Web, iOS, Android or our API.

A few years ago, we outlined how we were able to build a cross-platform image rendering pipeline to visually power our Android and Web app, which we then extended to cover the needs of our API. But we didn’t stop there. We extended this cross-platform library (the “Photoroom engine”, as we like to call it) to support other uses cases, most notably text rendering. This turned out a great success, and helped users of Photoroom ensure that their creation would look the same on all platforms that we support.

At the end of 2023, we set ourself a new, ambitious goal: we wanted to become the first, truly cross-platform, realtime image editor.

The first realtime cross-platform image editor

Platform-first development

One thing that we need to explain here. There are other applications that allow for realtime image editing across several platforms - Canva, for instance, springs to mind. But those products usually did not start as mobile applications. We started as an iOS app, and we fundamentally believe that our users keep coming back because the experience that we provide feels right at home on each platform that we support. Using Photoroom on iOS feels like using a native iOS app, because it is. And the same goes on Android. Our users are not feeling like they are using a web app disguising itself as a mobile app - because they aren’t.

In order to bring this level of quality and craft to our work, we believe it is paramount to use the tools and APIs the platform provider (Apple, Google, etc) makes available to its developers: we want to use native SwiftUI on iOS, and we want to use Compose on Android, not Flutter or some type of web-based technology that employ a one-size-fits-all approach to customer experience. Our users deserve better.

Taking stock

As we embarked on this realtime journey, we quickly realized that our existing approach to cross-platform development had its limitations. While our rendering pipeline was shared across platforms, other crucial aspects of our application - such as the document model and synchronization logic - were not.

While our synchronization code at the time was relying on a REST-based API (you could create, edit or delete documents by using simple HTTP endpoints), each platform had their own implementation of sync on top of it, to allow users to seamlessly edit documents as if they were local, even if their internet connection dropped temporarily. This was doing the job fine, but realtime editing is a different beast: the intricacies of conflict resolution and ensuring a consistent state at all times between all parties involved makes it really hard to get right in one implementation, let alone three of them.

We were quickly convinced that in order to bring this kind of feature, we needed a shared implementation of our document model and synchronization logic across all platforms. This would not only ensure consistency in how we handle real-time editing and conflict resolution but also completely eliminate the complexity of maintaining multiple implementations. This meant that the cross-platform "Photoroom engine" needed to expand its scope well beyond rendering.

Expanding the scope of our cross-platform engine presented new challenges. Our existing library was entirely synchronous, which worked well for rendering but wasn't suitable for the complex nature of real-time editing and synchronization, which is naturally I/O driven. We needed a way to share logic around something intrinsically asynchronous, something our current approach wasn't designed for.

Creating and maintaining a system for portable, asynchronous I/O in Rust, which would work across WebAssembly, Kotlin and Swift seemed like going one side-project too far, so we went looking for existing solutions that might help us. After a few days of extensive research, we found a promising open-source one.

Enter: Crux

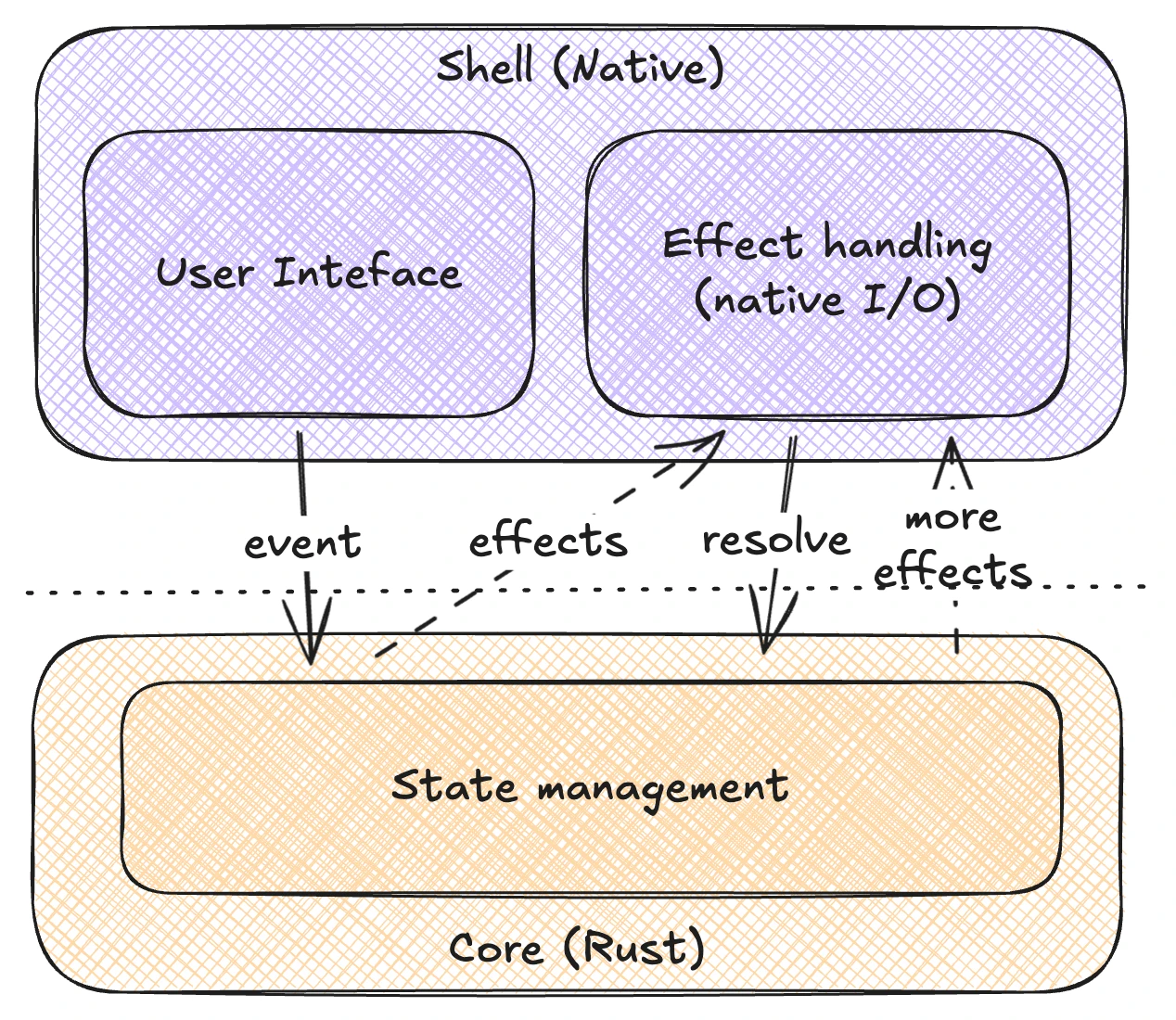

Crux is a framework for building cross-platform applications mostly in Rust, with a philosophy very similar to the one we just described: like Photoroom, it is built around the idea of platform native apps using native UI toolkits, but sharing a common core built in Rust.

In addition, the core in Crux apps can access asynchronous I/O, using a managed effects system. It allows the core to initiate and orchestrate the various I/O calls without actually performing them. The implementation of the I/O primitives (such as sending HTTP requests or handling WebSocket connections and messages) is delegated to the platform-native side of the app - this lets us use e.g URLSession on iOS to perform any kind of network request. This approach makes the core very easily portable, because it doesn’t require any common system interfaces to be supported in order to work, it essentially defines its own. As a side effect, it also means tests of the core logic are much faster and stable, because no I/O is happening, only plain data gets sent in and out the core.

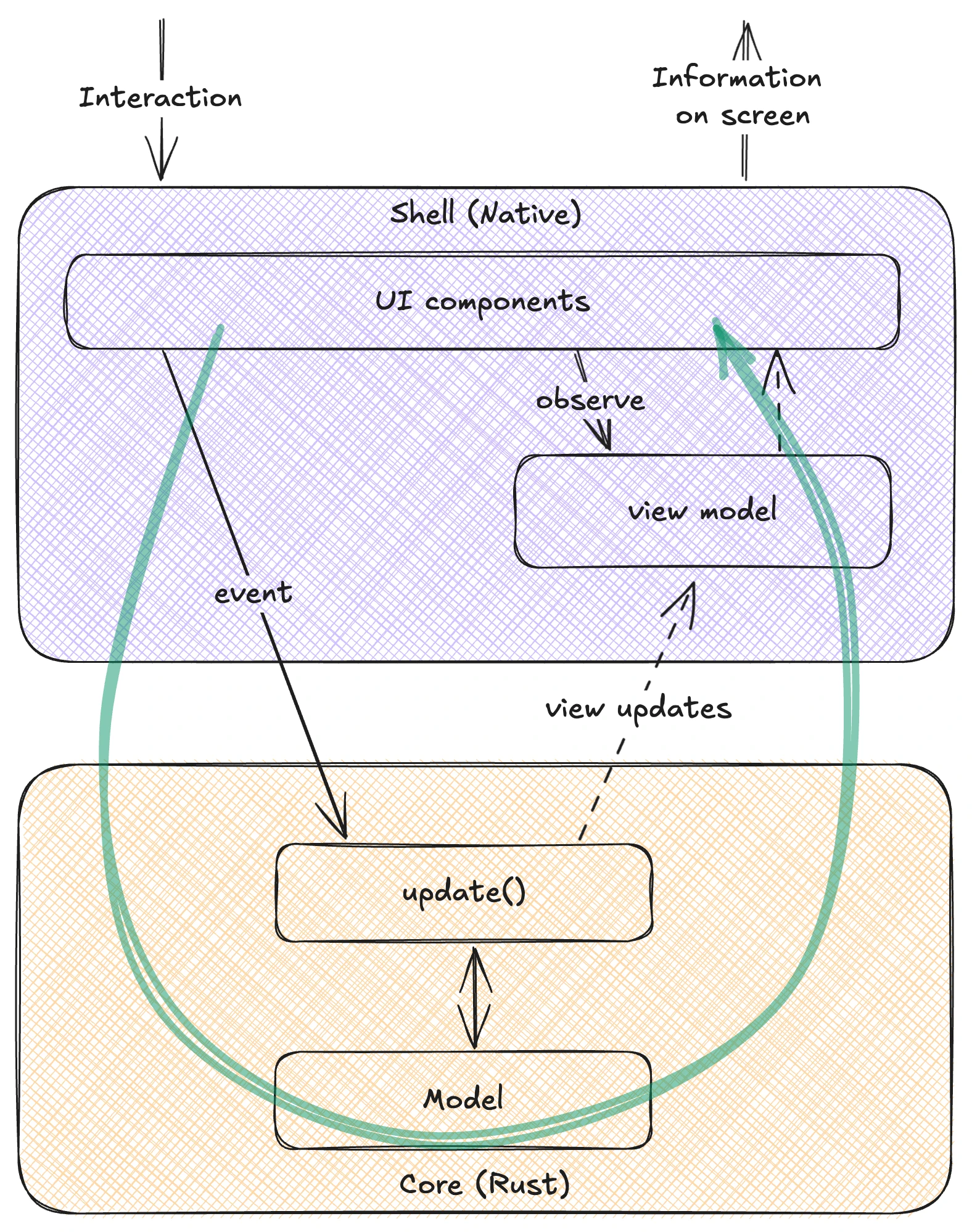

The other aspect that looked like a good fit was the unidirectional flow of data in the user interaction loop, inspired by Elm, Redux, and similar UI state management approaches. Rather than exposing asynchronous transactional APIs for the apps, where a user action triggers a function call which (eventually) returns data for a UI update, the two sides are fully decoupled: the user interactions create events, which are sent to the core. Separately, the core keeps an up to date view model, representing what should be on screen, which the UI can observe and show on screen using native APIs. This is really important for the overall design, because in the new real-time collaboration world, not all UI updates are a result of the local user’s actions. The decoupling of interactions and display update isn’t just a nice design pattern, it is now a requirement.

One of the technical challenges we were thinking about when looking for a good solution for shared asynchronous I/O was how to manage the concurrent execution in that setup, especially in a way that works both in WebAssembly, which is naturally single-threaded, and in the native apps which run async tasks and coroutines on thread pools.

Crux side-steps this problem entirely, by making the core synchronous and providing a data-oriented, message based interface with just two functions which look roughly like this:

fn process_event(event: Event) -> Vec<EffectRequest>

fn handle_response<T>(effect: EffectRequest, response: T) -> Vec<EffectRequest>The first receives an event from the app (in response to a user action) and returns zero or more “effect requests” - requests for some I/O to be performed. If the I/O request needs a response (most do, like HTTP or disk I/O for example), this is sent back to the core using the second function. Even the second function returns effect requests, enabling longer effect chains to happen.

Both functions are synchronous, they run the core logic and return immediately. The asynchronous loop is left to the native app to create and the native APIs handle the I/O, suspending execution and continuing when results are ready. This is ultimately what makes this system so easily portable and testable: it pushes asynchronicity to the boundaries.

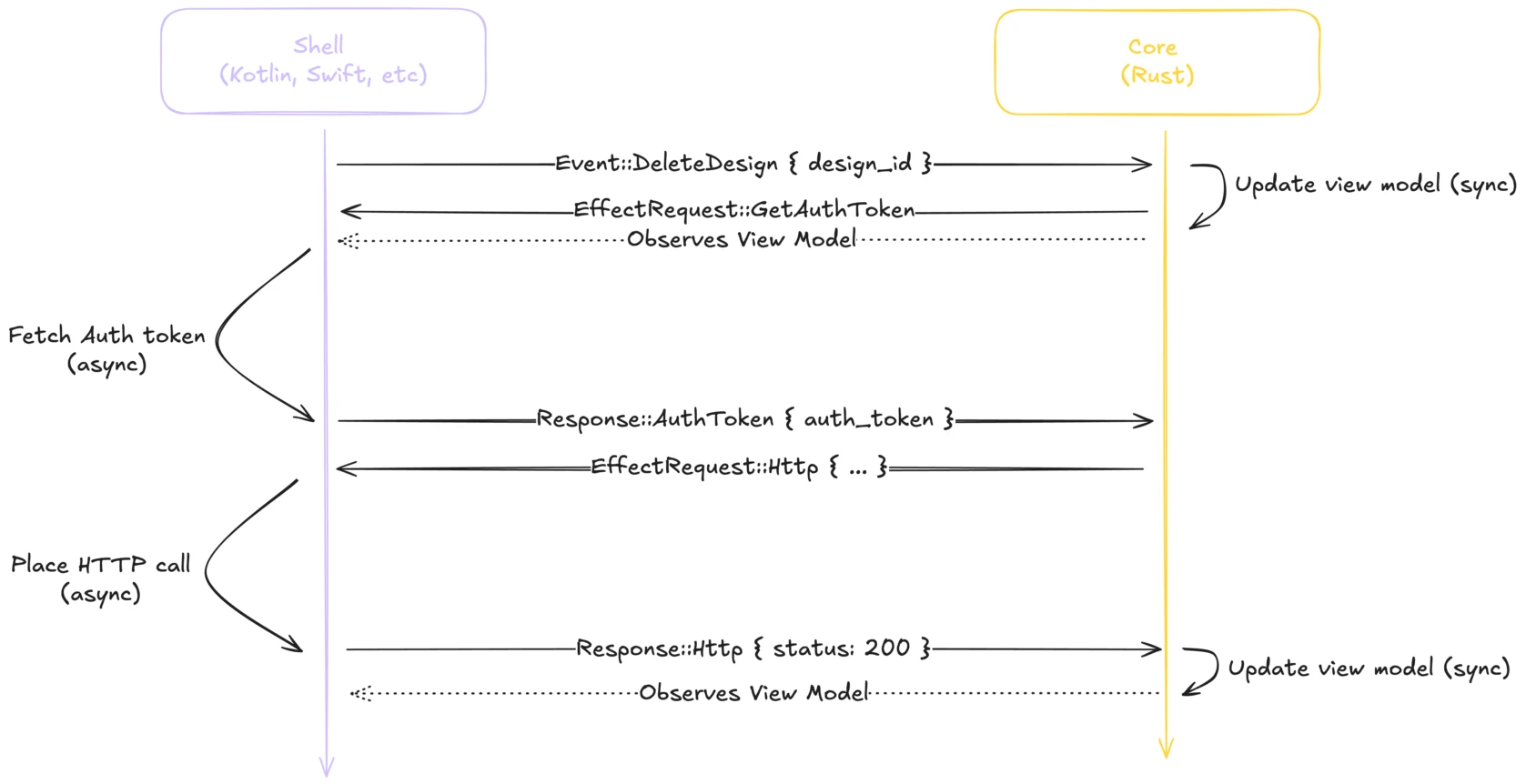

Here's a simplified example to better understand the interactions; Let's assume the user tapped on a button mapped to deleting one of their existing design. What needs to happen is fairly simple: we need to call an HTTP endpoint with the id of the design we want to delete and a valid auth token. This would look like this:

The shell will first place a call that looks like this

process_event(Event::DeleteDesign { design_id })During this call, the core will synchronously update its view model to let the user know the action has been taken into account. It can be either optimistically removing the design from the list, or marking it as 'currently loading' depending on the experience we want to provide.

This call will then return an array of effect with one element:

auth_request = EffectRequest::GetAuthToken

The shell will then fetch the auth token and refresh it if necessary to ensure it's valid, and continue by calling

handle_response(auth_request, Response::AuthToken { auth_token })During this call, it is unlikely the core will update its view model, as there is nothing to show yet

However, since the next step is to place the HTTP call, it will return an array of effect with one element:

http_request = EffectRequest::Http { method = DELETE, url = "https://internal.photoroom.com/designs/{design_id}" }

The shell will then perform the HTTP request, and call

handle_response(http_request, Response::Http { status: 200 })During this call, the core will update its view model to reflect the successful completion of the delete

And since this is the end of everything that needs to be done, will return an empty array of effects, thus ending the interaction.

It’s worth pointing out that these requests are fairly low level. For HTTP, for example, you can think of them as the inputs for calling fetch. While this just made calling fetch a fair bit more complicated, it allowed us to move all the code which calls fetch (and decides the arguments to call it with) into the engine and reuse it across platforms. Crux calls these I/O interfaces “Capabilities”, and provides a few common ones. We also built some custom ones, although not very many. The whole Photoroom engine uses less than ten of them, but they are called hundreds, if not thousands of times in the lifecycle of the app.

You can now see why we got interested in this model; It had a good answers for all of our key requirements – handled I/O across platforms, a simple threading model, and had a good approach to UI updates in a multi-user context. But given the level of change of direction it would bring, we needed a good way to trial it, and introduce it into Photoroom apps gradually.

In the next part of this series, we will look at Crux in more detail, and talk about how we slowly brought it into our “engine”.

Today

All of this happened almost 18 months ago, and today, the Photoroom engine handles the majority of user interactions around the editor and the content library, and especially everything supporting realtime collaboration. During that time, we consolidated our document model - building a single source of truth that gets vended to app developers through code generation, built a robust framework for fine-grained observability across the FFI, and completely abstracted sync and the editor to allow for the gradual introduction of live collaboration.

If you’re interested in more in-depth detail of how we built those features, you can read the future entries in this series! And if you happen to want to contribute to the effort, the team working on realtime is looking for a leader to shape the future of image editing: we are hiring remotely all over Europe.

Design your next great image

Whether you're selling, promoting, or posting, bring your idea to life with a design that stands out.